It's time to demand more from your coaches and administrators

Fans have power. Time to use it.

As protests against police brutality continue nationwide, we have an opportunity to put a microscope on problems in college sports. Current and former players are already doing this. Some examples from the past few days:

Iowa players shined a light on racist behavior by longtime strength and conditioning coach Chris Doyle.

Utah defensive coordinator Morgan Scalley was suspended after he admitted to sending a racial slur in a text, and a former Utah player said Scalley called him a racial slur in 2008.

At Clemson, assistant Danny Pearman also admitted to using a racial slur.

Head coach Dabo Swinney then released a 14-minute video response, which is probably best digested by this Bomani Jones thread:

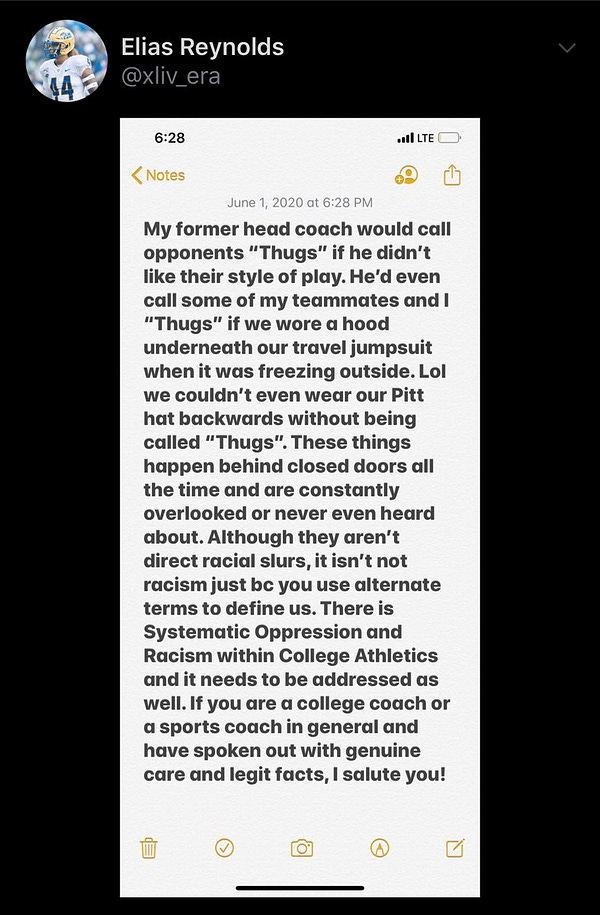

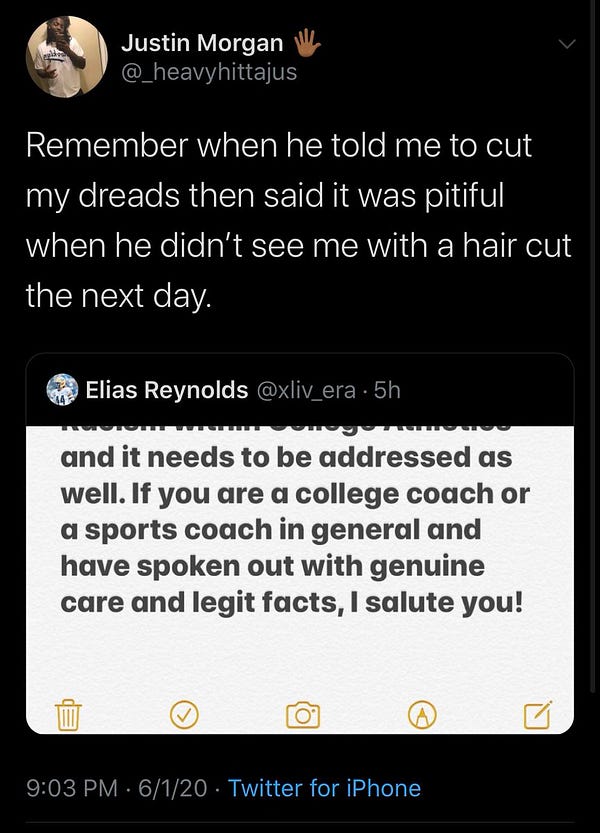

At Pitt, former players called out head coach Pat Narduzzi for calling players and opponents “thugs,” with one former player saying Narduzzi called him “pitiful” for not cutting his dreadlocks.

That’s not meant to be an exhaustive list. I’m sure there are more examples.

In the wake of these protests, many head coaches around the country sent out bland statements preaching unity, “standing against racism,” and lacking any specificity. Like this one from Nick Saban:

Standing against racism and listening to your athletes was already the bare minimum before these nationwide protests began, right? So what’s changed now? These statements miss the moment completely by refusing to acknowledge what people are protesting. They seem to take this tweet at face value…

instead of acknowledging 1) the choice between those two options should be obvious for any coach who cares about his players and 2) that any Fortune 500 CEO has the choice to side with employees and fight against racial injustice instead of just “avoiding controversy.”

“A lot of them must have been sincere in their outrage over Floyd’s death and their concern for their black players, but they seemed unfamiliar with the playbook,” writes Jesse Washington at The Undefeated. “The current racial crisis demands specific attention to the oppression of African Americans rather than statements like LSU football coach Ed Orgeron’s ‘I will not tolerate racism,’ especially for coaches with life-changing influence over thousands of young black men.”

Social media scorekeeping is not the point here, but some of the college sports world’s leading voices did add substance. Like South Carolina’s Dawn Staley, the UConn women’s basketball team and Ohio State football. Auburn’s Gus Malzahn showed up to a protest. (This too is not meant to be an exhaustive list. I’m sure there are other examples out there.)

Still, those examples were not the norm. So what happens now?

Fans do have power in college sports.

Fans have power. They buy tickets. They subscribe to the cable provider that allows them to watch their team on TV. A smaller number of them may donate enough money to pay your head coach’s salary.

There may be no better example of the power fans have than Nov. 26, 2017. That morning, reports surfaced that Tennessee football was nearing an agreement to hire Greg Schiano as its next head coach. What happened over the course of that afternoon was an exercise in many ridiculous things, but chief among them was the power fans have to hold a program accountable. After a day of protests, graffiti and bad tweets, the Vols announced they wouldn’t hire Schiano. The fans won.

At ESPN, Harry Lyles Jr. addressed some ways football coaches can enact meaningful change right now, including creating environments to encourage listening without retribution and banning dress codes that police what black players can and cannot wear.

At Florida State, after star lineman Marvin Wilson called out head coach Mike Norvell for overstating his efforts to address the protests with his team, FSU landed on a few reforms: raising money to send more black children to college, raising more money to send children from Tallahassee to college and making sure everyone on the team is registered to vote.

Norvell’s peers around the country shouldn’t wait for a player uprising just to make them follow through on the commitments they made when they entered the profession. As John Talty writes at AL.com, players have more power than ever. But fans can play a role in keeping their coaches and athletic directors on task too. After all, it shouldn’t be on the college-aged kids to fix the situation everyone else put them in. Fixing their situation should be on everyone who benefits from the labor they provide. You can write to your athletic programs just like you can write your congressional representative. Athletic directors have email addresses. Athletic departments have easily available staff directories too. I found my alma mater’s simply by googling “[alma mater name] athletic department staff directory.” Usually, this is not something fans utilize unless they are raging at the administration about a coaching search. I think we’ve just found a much more important topic.

Better yet, tell your local alumni or booster group that tailgates or watches games together to all send the same message. When your coach does that weird summertime statewide tour to hear from fans, talk to your coach about some of the things mentioned in the above ESPN story. If you’re the kind of person who donates money to a school’s athletic department, make your donation conditional on the school changing the way it treats athletes. You can make your voice heard.

If you enjoy college sports, you’re benefiting from entertainment with a rotten core.

Inequality is baked into the foundation of college sports, especially revenue-generating ones. In Division I football and women’s and men’s basketball, at least 45 percent of athletes are black and do not (legally) make money for their participation in those sports. Those athletes create generational wealth for head coaches, an overwhelming majority of whom are white. The revenue these athletes generate is what makes it possible for the other NCAA sports, all of which have a majority of white athletes, to exist.

So if you, like me, enjoy college football or any other NCAA sport, the very least you can do is acknowledge the thing you’re watching should not exist the way it currently exists. And instead of doing the very least you can do, you can do more than that!

Eventually, this should only lead in one direction.

Paying the players.

That’s not the only thing that’s important here, of course. All the rights athletes are fighting for right now are important. College athletic departments need more inclusive hiring practices, more safeguards to prevent abuse at the hands of coaches and countless other reform measures to treat athletes fairly. But this one issue tops them all.

If coaches really listen, really come down on the side of their players and really want to enact meaningful change that helps fix racial inequality wherever they can, that’ll mean eventually toppling the biggest boogeyman in their sport. There’s no way around it. That doesn’t necessarily mean coaches band together tomorrow to agree to cut their own salaries and give the proceeds to their players (though I think that would be great). It does mean coaches need to carve out space for athletes to profit off the revenue their labor creates. Making sure players get a cut of the revenue they generate is the ultimate destination. It’s simple.

Look, if Randy Edsall, a coach who had some of the more draconian rules I can remember seeing recently, can support paying the players…

other coaches can too. And so can you.

Thank you for reading The Slant. You can reach me with feedback, questions or story ideas at ryanmconnors11@gmail.com.