What the Big Ten's decision to cancel football really says about the Big Ten

One of the most powerful entities in college sports is hitting the pause button. But no conference is the moral authority in college football.

The Big Ten became the first Power 5 conference to officially postpone the 2020 fall sports season on Tuesday, about a week after it announced a revised schedule for college football.

The Big Ten’s announcement was the first from the Power 5 (or Autonomy 5), the conferences that largely control the sport’s decision-making at the highest level (the Pac-12, SEC, ACC and Big 12 are the others). Big Ten teams won’t play an actual football game until spring 2021 at the earliest.

The Big Ten’s announcement comes on the heels of similar decisions from other levels of the sport. The Ivy League, which participates in FCS football, punted on 2020 football last month. The MAC and Mountain West, both FBS conferences, announced in the past few days they too would wait until at least the spring to play football.

The Big Ten is doing the right thing for athletes by not playing football this fall. But once you dig in, there’s not a lot to praise.

The reasoning behind Big Ten’s decision is ostensibly that playing team sports, especially football, is not possible without risking player safety in a way university presidents did not feel comfortable. How do you play football during a pandemic? The conference’s leaders evidently still didn’t have a good answer for that question, probably because one doesn’t exist.

“Uncertainties” was a topic Big Ten commissioner Kevin Warren harped on multiple times in his appearance Tuesday on the Big Ten Network.

“A lot of the questions that we need to make sure that we have answered,” he said, “now that we were getting closer to really going to the next phase of practice and getting closer to actually compete, to have competition, is that there are just too many uncertainties to feel confident from a medical standpoint to proceed forward.”

Warren, later on:

“Based on the uncertainty surrounding the medical situation and having our student-athletes compete in fall sports, we just did not think it was prudent at this time,”

And again:

“There’s so much uncertainty,” Warren said. “As we ask questions, two weeks ago some questions were answered. But then you ask more questions and then maybe those questions are answered but then there’s new questions. And then you ask questions even today. And that’s not only in the Big Ten. That’s across the country and the world.”

And in the conference’s official statement:

“As time progressed and after hours of discussion with our Big Ten Task Force for Emerging Infectious Diseases and the Big Ten Sports Medicine Committee, it became abundantly clear that there was too much uncertainty regarding potential medical risks to allow our student-athletes to compete this fall.”

The sport’s leaders, to the extent that it has any, were waiting in the hope that America’s contained the virus to the point not just that that non-bubble sports are possible, but that football, probably the riskiest sport possible in our current situation, could be played. That hasn’t happened. The SEC, Big 12 and ACC are holding out hope for a season as of now, but there’s a lot they’ll have to figure out.

In this, and any, scenario, colleges have a responsibility to keep their players safe.

“Maybe people will not agree with the decision we’ve made today and I understand that,” Warren said. “I understand the passion associated with it, but we have a responsibility as a conference to make sure we’re doing everything that we possibly can to keep our student athletes in an environment where 1. they can get a world-class education and earn a world class degree and then compete athletically in a healthy, world-class environment.”

But if every decision the conference made were centered upon player safety, we wouldn’t have been here in the first place. The realities of the pandemic have been apparent for a while now, but schools brought players back to campus anyway, exposing them to other players (or students) who might have Covid-19.

(For people saying “schools are going to bring back regular students too!” well that also seems like a terrible idea.)

Shortly after Warren’s TV appearance, The Athletic’s Nicole Auerbach reported the conference was aware of at least 10 players with myocarditis, a rare heart condition.

Here’s how ESPN, which reported on the role of myocarditis in conference discussions over the weekend, described the condition:

The condition is usually caused by a viral infection, including those that cause the common cold, H1N1 influenza or mononucleosis. Left undiagnosed and untreated, it can cause heart damage and sudden cardiac arrest, which can be fatal. It is a rare condition, but the COVID-19 virus has been linked with myocarditis with a higher frequency than other viruses, based on limited studies and anecdotal evidence since the start of the pandemic.

The Big Ten commissioner downplayed the role myocarditis in the conference’s decision-making during his appearance on BTN.

“There’s been a lot of discussion of myocarditis as of late,” Warren said. “That’s not the primary reason [for canceling]. All of those items, from a medical standpoint, you have to consider. I know there’s been a lot of discussion about that. But overall when it comes down to it, it’s the litany of things that created this state of uncertainty that we need more clarity on from a health and wellness and medical standpoint. But again it’s sad. That’s a concern. Any time you’re talking about the heart of anyone, but especially a young person, you have to be concerned. And we want to make sure we’re doing everything we possibly can to keep our student athletes safe.”

Knowing all this, teams in the conference were still scheduled to practice on Tuesday until the cancelation announcement came out. While Warren did consistently note that there was no guarantee of a season, the conference let players, fans and coaches think playing was a real possibility for months, and hadn’t even publicly proposed a backup plan.

Despite health risks they knew about and health risks they maybe didn’t, teams in the Big Ten and across the country brought players back to campus to train with the hope of somehow pulling off a season. They did this because they needed cash. The Big Ten distributed over $50 million to each member school in 2018, an amount driven by football TV money. This is not a mystery, and not everyone’s exactly hiding it.

I’m trying not to generalize too much, but this whole decision fits with the Big Ten’s reputation as a pretend moral authority in college sports.

The Big Ten has a history of acting as if it’s a moral authority in college sports. Former commissioner Jim Delany, who made a $5.5 million salary in his final year in the position, once said he’d consider moving to Division III if schools were allowed to pay players. The league once floated the idea of proposing a mandatory redshirt year for all freshmen in football and men’s basketball.

Neither of those things would ever happen because the Big Ten’s No. 1 priority was generating as much money for its member schools as possible. The Big Ten is very good at this, hence the above $50 million figure. There would be no shame in generating lots of money as a business if you paid your workers equitably. But since the Big Ten is a college sports conference, its schools pay workers in college credits and perks, not in money. That’s where the whole act craters. All conferences say they are equally committed to academics and athletics, so when Warren says something like “We really do strive every day to be exceptional, both academically and athletically, but we also want to be exceptional in how we treat our student athletes,” it’s not surprising. But it’s still not true because treating the athletes exceptionally would involve allowing them to cash in on the rights to their likeness, and it would involve giving them some of the revenue their labor creates.

It’s also not clear how much information the Big Ten shared with its peer conferences before deciding to cancel.

“I know there’s been a lot of sharing of information and a lot of great articles that have been written in medical magazines, studies and I’m sure there will be many more,” Warren said on BTN.

This wouldn’t be the first time something like this has happened recently. The Big Ten was the first school to go conference-only with its 2020 football schedule last month, and Big 12 commissioner Bob Bowlsby said the Big Ten didn’t give any of its peers a heads up that the news was coming.

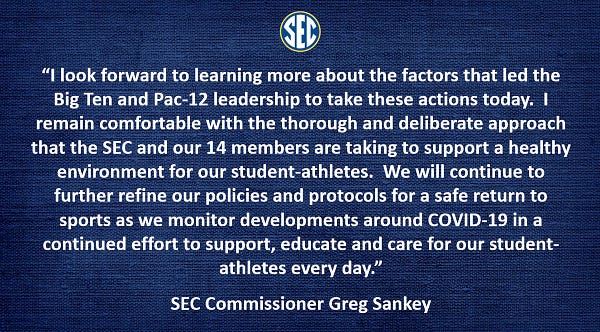

SEC commissioner Greg Sankey appeared to throw a dash of shade in his response to the news that the Big Ten was calling curtains on fall sports.

Deciding before other Power 5 conferences might allow the Big Ten to seem like the big important heroes who put education and safety first, regardless of whether that really the chief motivator guiding the conference. That’s not how college sports operate, though. No one comes out of this looking good.

Hey idiot, the Pac-12 canceled its season too.

Right, OK. Some of what I said above applies to the Pac-12 and some of it doesn’t. We’ll talk about Larry Scott in another newsletter.

If you liked this newsletter, I hope you’ll tell a friend. Follow along on Instagram here.